One of the most exciting parts of running Elhaz Ablaze for me has been curating our Guest Journal section. Sweyn originally wrote this essay in a Loki-like spirit for a very conservative (retro-)heathen journal which collapsed, as I understand it because of internal politicking, before it was able to publish his paper.

As such it was a surprise when he offered it to us here at Elhaz Ablaze but I knew immediately that we had to publish it.

I won’t say too much more by way of introduction – except perhaps that I hope to see a few sparks fly as a result of this little essay.

-Henry

Heathenry & Modernity: Some informal thoughts from a Heathen Technocrat

Sweyn Plowright

There has been much discussion in recent years of the negative aspects of the modern world. The very word “modernity” has acquired an almost derogatory connotation in some quarters. But what do we mean by “modern”? There are many variations, but essentially we understand it to mean the cultural current revolving around the technological progress following the “Age of Reason” or “the Enlightenment”, usually described as beginning roughly around three centuries ago.

There are also many variations in the way we define “Germanic Heathenism”, but we can broadly agree that it involves seeking spiritual fulfilment in the traditions and literature of our Germanic ancestors. The question now is whether these two forces are compatible. At the risk of sounding heretical to some, I would argue that they are not only compatible, but that modernity is in fact the most successful lineage of our ancestral culture.

Certainly, there are many things we can criticize in the modern world, but by rejecting it wholesale, we not only risk throwing the baby out with the bathwater, we also neglect our opportunity and responsibility to influence this world. We need to separate the positive key features of the Enlightenment plan from the commercialism, greed, and acculturation that has become a common, but not a necessary, concomitant of modern life.

The important elemental seeds of modernity can be found in the migration of Angles and Saxons to Britain. They brought with them their Heathen Common Law. This treasure of Germanic culture encapsulated the Heathen respect for custom, fairness, and the rights of individuals. Common Law was based on precedent, the accumulated wisdom of previous rulings, which could take local custom into account, while allowing judgements to evolve over time as customs and values changed.

If we look at Roman Civil Law, its focus is on protecting the State and the privileges of its citizens. It is set by legislation, and is relatively rigid. Any examples of fairness were really expedience aimed at keeping order. Citizenship was only granted to those who might be useful to the State, and this gave privileges, not rights. Many non-English speaking countries have legal systems modelled along these lines.

In much of Middle-Eastern history, laws were mostly based on religious strictures and superstitions. Harsh penalties were often inflicted for apparently victimless crimes, particularly for blasphemy. These laws were aimed at enforcing religious authority, and survive today in the Muslim Sharia law. A State practicing such laws will necessarily disadvantage individuals who do not practice the State religion.

By contrast, Germanic law had more focus on victim impact and compensation, redressing the balance or wyrd. English law even developed safeguards to protect individuals from the law, in the form of due process and the presumption of innocence. With the onus on the prosecution to prove guilt, there was a focus on evidence-based inquiry.

It is no accident that the person often considered the founding figure of modernity was an English lawyer. Around 1600ce Sir Francis Bacon was considering the question of the laws of nature. Academics had always approached this from a philosophical perspective. They thought that they could deduce the laws of nature by philosophical ruminations alone. Bacon could see the futility of this approach.

Bacon was also aware of the work of alchemists. They were trying another method to discover the workings of nature. However their experiments were fairly random, with no plan or framework to form and test ideas, they tended to collect unrelated facts by chance, without really understanding what they saw. They were another reason that academics rejected, and looked down upon, the idea of experimentation.

Armed with the pragmatic common sense and experience of the Common Law, Bacon realized that only by combining reason and experiment could the secrets of nature be discovered. He likened the investigation to the questioning of a witness in court. The questions could be framed in terms of experiments, and reason is employed to lead to further questions, to create a consistent and more complete picture. He saw this as the most effective way to free people from being completely at the mercy of nature. Ignorance was the cause of most suffering, and as he put it “knowledge is power”. He was specifically talking about the power to use the knowledge of the laws of nature to improve our situation. This was the beginning of the systematic development of technology based on directed research.

The word “law” comes from the same Germanic root as “to lay”, something that is laid down, or layered. There was a concept of a primal or fundamental layer “orlog”, which consists of those laws that, by definition, can not be broken. Some may think of this as a mystical concept. However, there was no such division between the physical and the mystical for our ancestors, even including Bacon. That artificial divide was a product of Judeo-Christian Gnosticism, which saw the physical world as unclean. Bacon saw natural law as an expression of the divine, much as most Heathens do. He is sometimes portrayed as advocating domination over nature, but if you read his works more fully, this is manifestly untrue. He clearly proposes that understanding, and working with, the laws of nature will allow us to live more comfortably and capably in this world.

If our ancestors lived a relatively tough life, it was not because they did not value material culture and its advantages. They were obviously proud of the skill of their smiths and shipbuilders. They made the effort to create fine homes and clothing if they could afford it, and traded or raided to create the wealth to do so. We can see this also in their description of the Native Americans as pitifully poor, because they did not possess steel weapons, or wear cloth. Germanic people generally have always been early adopters of technology, and their transition to creators of technology was very natural.

Another aspect of the Common Law and its culture was its sense of fairness and tendency to value the individual. This was kept alive in the stereotypical English expression “it’s just not cricket” if someone takes unfair advantage. We know that an almost fanatical love of fairness is an ancient part of the culture. At the battle of Maldon, the English Earl would not slaughter the Viking army as it crossed a ford. Instead, he waited until they were in a fair position on the field, even though he knew that the odds were against him. He died with all of his men, but became a shining example of English fair play in the epic poem. The idea has not diminished over the centuries. In a recent poll to determine the elements that define the Australian culture, the most popular item by far was the expression “a fair go”.

This concept of fairness is the true origin of the idea of individual rights, and the Western democratic idea of freedom. Because these are so deeply rooted in our culture, we tend to take them as self-evident and universal values, but some non-Western countries have argued that human rights are not self-evident, and that they are an example of Anglo-Saxon cultural imperialism. This argument is particularly heard from those countries under scrutiny for their mistreatment of ethnic minorities, or other groups with views different from those of the political authorities.

It seems that the Heathen notions of freedom extended to religion. Heathens did not recruit members, and they do not seem to have disadvantaged those of other beliefs. When Christianity came along, Heathens lived quite comfortably along side Christian neighbours, and even spouses. It was not until the Church gained the support of the ruling powers, and revealed their fundamental intolerance for other faiths, that Heathen resistance was aroused (alas too late).

Christianity suppressed alternative ideas wherever it could. It was not until the emergence of English Enlightenment thinkers like Locke, and his greatest Continental fan, Voltaire, that it was possible to argue that persons should only be prosecuted for their actions, not for their beliefs. These concepts of religious tolerance were held in high value by the creators of the American Constitution. The independence of the State from religious interference required the institution of secular government. It is this that gives Heathens the legal right to practice without persecution or disadvantage.

Thomas Jefferson saw the importance of this separation of Church and State, including the role of English Common Law as one of the few surviving ancient systems independent of Christianity. When Christians tried to claim a moral victory by stating that the legal system was based on Christian rules, he refuted this by pointing out its Heathen origins.

“ For we know that the common law is that system of law which was introduced by the Saxons on their settlement in England, …. This settlement took place about the middle of the fifth century. But Christianity was not introduced till the seventh century; the conversion of the first christian king of the Heptarchy having taken place about the year 598, and that of the last about 686. Here, then, was a space of two hundred years, during which the common law was in existence, and Christianity no part of it.” Jefferson, 1814.

In many ways, the values developed by the Enlightenment thinkers can be seen as a real renaissance of the Heathen Germanic culture of freedom, law, pragmatic reasonableness, and individual rights. The success of this culture is obvious in the way it has become that basis of the values of the free world. The English language spread along with it, and has become the language of international trade, science, and politics to a large degree.

So, while it is worthwhile connecting with nature and our ancestors, camping out and dressing in Viking gear at feasts, it is not necessary or productive to make that the major focus of one’s life. In the larger modern world, a world of our own making, we need to be participants. We need to be there to safeguard and carry forward the legacy and values of our Heathen ancestors as they have come down to us in the form of modern democratic freedoms. Something our ancestors were always prepared to fight for.

Having served in the military as a Combat Engineer in counter terrorist roles, having worked in various civilian security positions, and for the last couple of decades as a network engineer in large corporate and government IT environments, working in network security and network forensics, I have come to appreciate that there are many who seek to undermine our way of life, the Enemies of Freedom are not just a paranoid bogeyman invented by the Government to keep us in line.

We all know that governments have their own agendas, but they have a primary duty to protect their citizens. If the very measures they take to combat this threat should lead to a restriction of our liberties, it is up to us to us all to make such measures less necessary. Our own complacency and lack of involvement gives governments little choice. Do we accept the inconvenience of increased surveillance, or the inconvenience of occasional bombings in our cities, and in what balance?

Education is the key, both at home and abroad. Ignorance and complacency makes our citizens look frivolous and decadent. Our relatively easy lifestyle is envied by less fortunate people, and so becomes a threat to dictatorships and religious regimes, whose people may be tempted by ideas of democracy. We are painted as evil seducers, and the people are not educated enough to question that. This, in large part, motivates the hatred behind attacks by extremists.

Governments and corporations have much to answer for in the spread of mistrust and ignorance amongst their citizens. The UK played down the BSE threat. China did the same with SARS. The US & Australia until recently have largely ignored the evidence for global warming. The tobacco industry covered up the glaring evidence of a lung cancer link for years. This not only shakes public confidence in any kind of “authority”, a far more serious consequence is that it creates distrust and misunderstanding about evidence based knowledge itself. This encourages scientific illiteracy, and leaves people vulnerable to the various cults of unreason, pseudo-science, New-Age-ism, and fundamentalism.

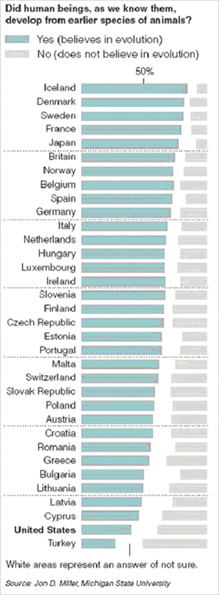

It is a damning indictment that in the most powerful nation of the free world, nearly half the population does not accept the idea of evolution. After a century and a half of intense debate and observation, evolution much as Darwin described it, is perhaps the most solid, tried, tested, and easily understood process we can witness in nature. Yet ironically, most of these Christian Creationists are quick to label Muslim fundamentalists as backward for their unenlightened views.

The rise of these and other forms of irrationalism pose a real threat, not only to our Enlightenment heritage, but ultimately to our freedom to practice the older parts of our heritage. The plain fact is that we can not separate our Heathen heritage from its Enlightenment descendant. Our Enlightenment heritage is our connection with our ancestral culture, and the frame of modernity in which most of us must practice our Heathenry.

There is a line of thought that we must somehow erase the experience of the last few centuries, and regress to an idealized vision of tribal society. That we may somehow shut out the real world and form “Asatru Amish” type communities. As nice as it may be for the privileged few to use log fires for heating and cooking, this would not be ecologically responsible or sustainable on a larger scale, adding to deforestation and pollution. But apart from the practicalities, such isolationism is more likely to lead to an out-of-touch and cultish form of Asatru, against which our next generation is bound to rebel. This may be the right path for a minority of Heathens, but it is not one that is likely to be productive for most.

In reality, we can never escape the influence of the wider world. We just have to adapt to it, do our bit to change its less wholesome aspects, and lead by example in keeping to our own standards and traditions. The Enlightenment framework is one that can accommodate most cultures. Only those that actively discourage democratic freedoms will have trouble adapting. In this respect, there is no reason that we can not continue to value cultural diversity and tradition, within the overarching framework of modern democracy, our own Enlightenment heritage. This is particularly true for Heathens, who share the same Germanic cultural roots as the Enlightenment.

Having a science background, and working in a high tech industry, I used to have some trouble reconciling this life with that of the heroic ancestors I admire. However, in their pioneering spirit, and forward looking enthusiasm, I can now see a deeper resonance. In the founding of England, Iceland, and America, we can see distinct parallels in the aspirations of exploration, freedom, fairness, and a better future. While I treasure my own mail coat and axe as fully functional reminders of my ancestors, I am happy to offer my inherited attributes of tactical cunning, and implacable ruthless determination, using modern weapons to help neutralize the threats to the freedom of my descendants.

Most of us have used the Internet to make Heathen ideas more widely available. Few of us have ridden a horse to gatherings. Technology and secular government have allowed Germanic Heathenry to flourish, and we have our Enlightenment ancestors to thank.

In the end, there are many ways we can be true to our Heathen heritage, but for those of us like me, who happen to be Heathen technocrats, be proud in the knowledge that you are fulfilling an important part of our cultural heritage.

Further Reading:

Porter, R. Enlightenment: Britain and the Creation of the Modern World. Penguin. 2000.

Henry, J. Knowledge is Power: Francis Bacon and the Method of Science. Icon Books. 2002.

Kramnick, I. The Portable Enlightenment Reader. Penguin. 1995.

Francis Bacon: The Essays. Penguin Classics. 1985.

John Locke: Political Writings. Penguin Classics. 1993.

A reflection of a country’s susceptibility to irrationalism? Note that the Scandinavians are the most free of this problem. Turkey is the only modern nation to rate worse than the US.

A reflection of a country’s susceptibility to irrationalism? Note that the Scandinavians are the most free of this problem. Turkey is the only modern nation to rate worse than the US.

Rock on! What a breath of fresh air…I don’t see the practicality of Amish Asatru on a large scale, either.

This is the 21st Century. The Folk need to learn to deal, and evolve, as well, or I fear they’ll end up becoming like the dodo bird, a joke AND extinct.

IMO, to be a living breathing religion, or path, you have to take the past and use it as your foundation, but you also have to build upon it…incorporate new ideas and practices.

Our ancestors would NOT be practicing the same way now as they did then…and to think that they would is to have your head in the sand.

Thank you Sweyn!! Much like I have thought, but couldn’t put into words.